There’s so much that goes into training for a marathon, but learning how to pace yourself correctly for race day may be *the* most important element. Think about the elites: When they’re running a marathon, the actual racing doesn’t usually start until they’re around 18 to 20 miles in, or digging deep for that last 10K.

Anyone who’s ever run a marathon will warn you against going out too fast, or tell you that you should try to run the second half faster than the first (negative splits are so much easier said than done). But there is an actual method for training to pick up the pace so far into the race: It’s called the 10/10/10 method.

The 10/10/10 approach to the marathon calls for splitting the race into three separate sections: the first 10 miles, the second 10 miles, and the final 10K. 'To paraphrase the great words of Nike Run Coach Julia Lucas, run the first 10 miles with your head, the next 10 miles with your training, and the last 10K with your heart,' says Jes Woods, a Nike Run Club Coach in New York City who implements the 10/10/10 method with the marathon runners she coaches. Let’s break that down a little further.

The first 10 miles (16kms).

Running the first 10 miles with your head means being smart, being patient, and listening to your coach. 'You want to make a conscious effort to hold back and run the first 10 miles at a pace that’s slightly slower than your goal marathon pace,' says Woods.

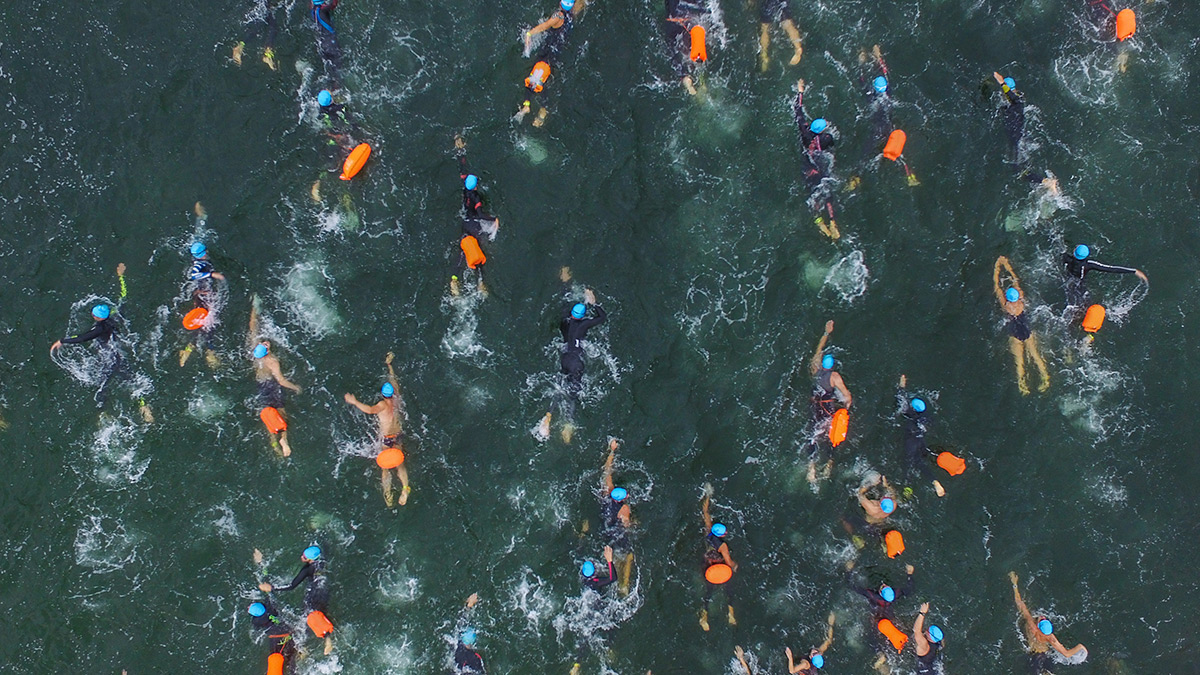

It’s hard, for sure—there’s a boat load of nervous energy at any marathon start line, and it’s extremely difficult to not get swept up in the excitement or start weaving around the hordes of runners to find your space. But taking the first portion slow means you’re also giving your body a chance to properly warm up and adjust to the running ahead, because chances are, you just stood in a corral for some time anxiously awaiting the gun.

You’re being strategically conservative with this method to ensure (or ensure as best you can) that you don’t go out too fast and die a slow death,' says Woods

The next 10 miles

TRunning the second 10 miles with your legs is all about trusting your training, says Woods. 'Let your body do what it has been trained to do,' she says. 'This is where you want to hit goal marathon pace like a metronome. Let it feel rhythmic and settle in.' You know this pace; you’ve trained for this pace.

At this point, your legs should be feeling good—after all, you just ran 10 miles at a pace slightly slower than the goal marathon pace you’ve been training at. Ease down on the gas pedal until you’re cruising at goal marathon pace, which your body should feel accustomed to. 'Mentally, you now "only" have to run 10 miles at goal marathon pace' says Woods—and any psychological tricks can help at this point in the race.

The Final 10km

Running the last 10K with your heart should be pretty self-explanatory: This is where you let it rip. 'Your strength doesn’t come from your body, it comes from your heart—OK, and that fire in your belly asking you, "How bad do you want it?"' says Woods.

The last miles should be your strongest miles following this method. “This is your time to surge and start knocking down some roadkill—which sounds aggressive, but I think there’s no cooler feeling than picking off runners one by one in the final miles of the marathon,” says Woods (remember, any psychological trick can help!). If you’ve been patient (during those first 10 miles) and followed the plan (during the next 10 miles), the final 10K is your time to shine.

How to Train to Race 10/10/10

First, in the same way you might try running negative splits during your weekly long runs, trying this method out in training is a good way to prep your body for race day. 'Once a month, you should practice a long run that includes a number of miles at goal marathon pace,' says Woods. For example: first 10 miles easy, last 5 miles at goal marathon pace. 'Your long runs should always start off slow then gradually progress,' says Woods. That’s going to teach your body to practice patience, ease into race pace, and finish strong.

Then, add in some strategic speedwork. Most marathon training plans call for one or two days of speedwork a week. Woods suggests incorporating split 800s—repeat efforts where you shift from running 400 meters at marathon pace, then 400 at 10K pace. 'That drastic gear change is going to help you practice turning over your legs and running fast on tired legs.' And that—plus the heart—is really all you need to close in on the finish line.